Embracing the “Overly Confessional:” Scholar-Fandom and Approaches to Personal Research

Tom Phillips / University of East Anglia

[T]he scholar-fan must still conform to the regulative ideal of the rational academic subject, being careful not to present too much of their enthusiasm while tailoring their accounts of fan interest and investment to the norms of “confessional” (but not overly confessional) academic writing.1

Matt Hills’ account of the responsibilities of a scholar-fan suggests that although there is scope for personal accounts within academic writing, boundaries should be drawn to prevent work from becoming too personal and therefore undermining the author’s credibility. Hills’ observation suggests that a little personality can inject verve into a potentially staid academic piece, but there exists a real danger that in revealing ones thoughts and feelings to peers academic authority and capital can be lost. However, it feels apt that Flow, where ‘non-jargony, highly readable pieces’ are encouraged, is where I come out and declare not only the influence my own scholar-fandom has on my work, but also argue that embracing an “overly confessional” approach to my academic writing is integral to the fidelity of my research.

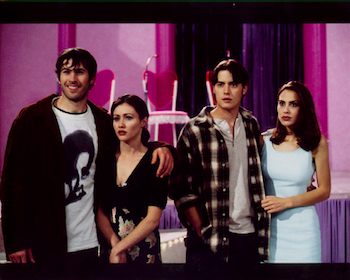

I have been a fan of filmmaker Kevin Smith since 2002, when I first watched his film Mallrats (1995). Following that I chose to primarily articulate my fandom as a consumer—buying Smith-related DVDs and merchandise, visiting locations from his films in New Jersey, and attending Q&A events in London. Latterly, my PhD thesis, Confessions of a PeepingTom: Kevin Smith Fandom and Online Community, uses my fandom as a springboard to launch into debates about the nature of fan practices, engagement with cultural practitioners, and the boundaries of online “community”.2 My chosen methodological practice of qualitative participation and autoethnography closely follows Robert Kozinets’ model of netnography, at the core of which he notes ‘is a participative approach to the study of online culture and communities’.3 In taking a participatory method to interrogating online Smith fandom, I have eradicated the lines between my role as a Kevin Smith fan and a Kevin Smith scholar. This article will subsequently question the validity of these classifications, and whether use of the term “scholar-fan” is appropriate.

Dana Bode states that ‘In my online life, I wear four hats: professional writer, reader, fan fiction author, and academic’, and I too regularly subscribe to this multiplicitous analogy. Nancy Baym notes, ‘Digital media seems to separate selves from bodies, leading to disembodied identities that exist only in actions and words.’4 With the apparent ubiquity of one’s “open” online presence, these disembodied identities can begin to merge, and differentiation between ones “hats” can begin to subside: academic, fan, and personal identities collapse into one.5 While this may not directly adhere to Hills’ concept of the overly confessional, allowing one’s “personal” self to be at least accessible to an academic audience has implicit connotations of unprofessionalism and the loss of academic authority.6 Although this may be a danger most academics would surely be keen to avoid, I would argue that in some cases a lean towards openness and individuality can in fact lend greater academic authority because of the personal attachment and investment to the subject.

For example, as part of my participatory approach to my Smith fan culture research, I began posting on his official message board in early 20107, with my entrée stating not only my academic intentions, but also highlighting my relative fan cultural capital. Within this initial post, I revealed that I had already posted to a previous iteration of the message board in 2003, seeking to be as transparent and honest as possible with potential research participants. Reflecting upon this process in a supervisory exercise, I detailed how my initial dealings with fellow fans, long prior to postgraduate study, revealed an early form of scholar-fandom. Based on an authorship study I had written at A2 Level, I introduced myself with the intention of portraying myself as a scholar-fan.8

However, the post received no replies, and in my work I reflected how my scholar-fan approach had failed to engage other fans, and potentially deterred them from interacting with me. However, as I would later concede to my supervisors (and again during a conference paper) this was actually my second post – my first being my contribution of “girl advice” to a poster having relationship problems. On the occasions I have made this disclosure, the revelation has generally elicited laughter from the audience. Making this fact known, and receiving this response is a somewhat embarrassing occurrence – here the musings of my eighteen-year-old self have come back to question my academic integrity in the name of ethical transparency. Yet despite the potential for embarrassment, I have continued – and will continue – to broadcast this incident, as I think it highlights a pertinent example of the overly confessional as a research practice to be encouraged.

In deliberately emphasising the over confessional myself, I set the parameters for what can be considered academically “appropriate” for my work. By confessing to an extreme scenario, “regular” scholar-fan activities are rendered less questionable, and embarrassing anecdotal evidence can be used to contextualise one’s relative academic authority. This juxtaposition results in moments where a potential ‘sadly celebratory tone’9 — a danger inherent to scholar-fans — is tempered by the inclusion of material that can be regarded as personally embarrassing, rather than professionally questionable.

The notion that questionable levels of personal taste within academic writing can be moderated by even further personal material is likely to be contentious. Part of the issue here is that opinion of how engaging personal research is likely to be is highly subjective. Hills notes that in the moments of scholar-fan embarrassment:

…we can see the mechanisms of a cultural (not merely subjective) system of value at work. It is a system of value which powerfully compels subjects to strive to work within the boundaries of “good” imagined subjectivity, or face the consequences of pathologisation.10

Hills’ observation sheds light on the value judgements academics are prone to making, and also makes a clear case for arguing that the personal can be considered “good” as well. To that end, does stimulating academic work necessarily have to adhere to the constraints of “proper” academic writing? Furthermore, if we are discussing the extent to which research must maintain a strict professionalism, does the argument itself have to be professional? Am I “allowed” to argue for personal academic accounts because I find them interesting and relatable, or must one adopt an academic authoritative scribe before they can attempt to interrogate it? More pressingly, will this article be taken seriously despite me mugging for the camera?

The scholar-fan approach to academia is wrought with difficulty, and striking an adequate balance can be an unenviable task – the reception to this article will determine the extent to which this is true. However, maintaining an objective, detached approach is arguably just as challenging. Considering this brings into doubt previous value judgements about the nature of personal writing – if both methods require that care must be taken, one cannot necessarily be considered more academically sound than the other.

By examining the way in which embracing the overly confessional can add to a writer’s academic authority, I have demonstrated that Hills’ assertion that the scholar-fan must still ‘conform to the regulative ideal of the rational academic subject’ is no longer a requirement. Whether considering oneself a scholar-fan, aca-fan, or researcher-fan, perhaps it is time to reassess these labels, and whether they are still needed. In questioning the value judgements as to what constitutes “proper” academic writing, it is also worth questioning whether it is necessary to even categorise researchers in such a manner, or ask if we are all simply just researchers adhering to varying degrees of the confessional.

Image Credits:

1. PandaJenn, ‘Confessions of a PeepingTom Logo Commission’.

2. Mallrats (Kevin Smith, 1995). Gramercy / Alphaville / View Askew.

3. Photo property of Tom Phillips

Please feel free to comment.

NOTES- Matt Hills, Fan Cultures, Routledge, 2002, pp.11-2. [↩]

- The term “community” is a contested term, particularly when it is applied to an online context. See David Bell, An Introduction to Cybercultures, Routledge, 2001, pp.92-112, for an account of some of the debates. [↩]

- Robert Kozinets, Netnography, Sage, 2010, p.74. [↩]

- Nancy K. Baym, Personal Connections in the Digital Age, Polity, 2010, p.105. [↩]

- For example, my own “open” presence spans my research blog, participation on Kevin Smith’s board, and Twitter, Facebook, and Academia accounts. [↩]

- See, for example, Hills, Fan Cultures; and Alexander Doty, Flaming Classics: Queering the Film Canon, Routledge, 2000, for discussions of the relationship of objectivity to academic (and scholar-fan) authority. [↩]

- At the time http://www.viewaskew.com/theboard; now located at http://www.theviewaskewboard.com. [↩]

- Though not actively recognising myself as such at the time. [↩]

- Bambi L. Haggins, “Apocrypha meets the Pentagon Papers: The Appeals of The X-Files to the X-Phile”, Journal of Film and Video, v.53, n.4, Winter 2001-02, p.25. [↩]

- Hills, Fan Cultures, p.12. [↩]

Well done, sir!

Outstanding, Sir!

Interesting article. Are we not all scholar-fans/researcher-fans? Do we not embark on projects that interest us, on at least a very basic level, which soon turns into a more obsessive level? I’m a fan of everything I do. However, I have very little interest in placing myself front and center in my research/writing. Is this fandom thing a question of degree? If not, it’s a moot point.

Greg DeCuir, Jr.

Faculty of Dramatic Arts, Belgrade

Hi Greg, thankyou for your comments.

I think you’re absolutely right – that surely all researchers take on projects that interest them in some way. However,I don’t think it is necessarily a case of researchers being fans of everything they do. Fandom I think connotes a sense of fondness for the subject at hand. Instead, I think it is probably more the case that all researchers are to some degree passionate about what they are studying, and it is their prerogative to determine how much of that passion they reveal in their writing.

I think that many academics–not all–begin as fans of the work(s) that they engage in their projects. (Ideological critics, for instance, analyze texts they don’t necessarily enjoy.) However, the notion of the confessional illuminates a key distinction. The goal of scholarship, to my mind, is to bring about a greater degree of understanding about an aesthetic object and/or its contexts or to generate knowledge. Academic writing used as a diary often only illuminates its author. We must determine if the findings have merit. One’s fondness for their profession or subject matter seem questionable grounds to stake the significance of one’s pursuits.

Hm, interesting. I’ve asked myself similar questions, e.g. if objectivity or even intersubjectivity should or can still be an academic ideal and what other forms of generating knowledge we may have at our disposal, if we only look in the right place. I haven’t found anything yet, so I stick to intersubjectivity, which means reciting and valuing my own experiences and that of others as well as trying to summarize and generalize them where possible, so that I can form a tentative conclusion or even theory for a very localized part of my (fan) subject, always acknowledging that it is only true for the circumstances I described.

It can be very frustrating at times, because you always know the connections you see are only the connections you see, but I infinitely prefer this very localized form of knowledge generating to more generalizing assumptions, which by definition exclude so much more. Maybe we should stop writing because we think what we have to say is/should be important to others (in the same fandom, in the same academic field etc.) and start doing it because what we have to say is important to us, but I don’t know if that is even possible. Sometimes I think that it is in fandom, and that this is the thing I love so much about it, but maybe I’m wrong *shrug*

Anyway, sorry for getting distracted by a tangent; I’m a german student writing her thesis in a field which calls itself “germanistische Literaturwissenschaft” (german literary studies) but has next to no idea that something like fandom and fanfictions even exist. It means I have an awful lot of explaining and defining to do (even if I might not want to), and essays like yours are a great help with that. So, in good fandom tradition: Thanks for sharing! ;)

Interesting article.

But, how does the aca-fan approach/attitude to media and popular cultural studies can help to remedy the general ‘crisis’ in the Humanities while many departments have to face alumni/funders who are no longer convinced that their contribution is worth spending?

Multatuli, Amsterdam.

I must admit, I rather like this article, given my own changing positions in regards to academic writing and fandom. You raise some very good questions, such as: ?��Ǩ?�?��Ǩ��does stimulating academic work necessarily have to adhere to the constraints of ?��Ǩ?�proper?��Ǩ�� academic writing??��Ǩ�� I?��Ǩ�Ѣm not sure when, but at some point I became a firm believer that, as you put it earlier when describing Hill?��Ǩ�Ѣs approach that “?��Ǩ��there exists a real danger that in revealing ones thoughts and feelings to peers academic authority.?��Ǩ��

Before my latest class in film theory, I do not believe I ever encountered a situation wherein I had to write a critical essay that in fact included what you might term the ”overly confessional”. My essay included a look at my own personal life history, which I tied to a growing interest in the development of new media technologies and its effects on modern cinema. This was much different from my traditional examination of cinema in as much objective, cold and rational manner as possible.

In part, I developed my style out of a desire to distinguish myself from ‘film reviewers’, that majority of whom do not write what I consider actual criticism. Most do not support their opinions with actual evidence and evaluations of such things as acting, cinematography, etc. Instead, they simply discuss how the film made them feel and what they ?��Ǩ��liked?��Ǩ�Ѣ about it.

I often found this to be unprofessional and pedestrian, as well as inconsistent – reading an article on RottenTomatoes.com, I was amazed how a critic could praise one film for the very reasons he would condemn another. Similarly, I realized that critics who were also fans of certain films would constantly allow themselves to overlook their treasured film?��Ǩ�Ѣs flaws, not giving others a similar pass. So I chose to deliberately avoid this approach.

If film critics write predominantly in the ?��Ǩ��academic?��Ǩ�Ѣ style, while reviewers in the ?��Ǩ��fan?��Ǩ�Ѣ style, I now find that a balance of the two – the aca-fan approach – can certainly be a viable alternative. One of my favorite critical film books is called ?��Ǩ?�Hollywood Asian?��Ǩ��, which I find is an example of aca-fan writing that embraces the ?��Ǩ��overly-confessional?��Ǩ�Ѣ.

Honestly, what is ?��Ǩ��proper?��Ǩ�Ѣ academic writing anyway? Who exactly set the standards for what we consider to be professional critical writing? A critic?��Ǩ�Ѣs subjective and emotional state registers within the text he delivers, no matter how objectively he situates himself after all.